150th anniversary of Golden Spike celebrates Utah’s piece of history

Published

5/10/2019

We all remember those times when it seemed like Utah was the center of the media attention. It felt like the state was a little bigger than its moderate population and isolated geography would indicate. Most can list those times when it seemed as though the country was focused on us – the 2002 Winter Olympics, NBA finals in the late 1990s, the Cold Fusion debate, and don’t forget about Donny and Marie!

While those times did generate attention, it can be argued that as far as lasting impact, it can be hard to surpass the party of 1869 in Box Elder County, when driving a nail solidified Utah’s place on the map.

It began as a dream of sorts as far back as the 1830s, to have a faster way to get from the east coast of the United States over to the west coast. Gold fever associated with the California Gold Rush in 1849 only intensified the need to speed up the 4-8 month trip with options of either sailing around the tip of South America or risking it all for a shorter distance, but more difficult trip on wagon trail across the country.

Everyone knew this trip had to be completed by rail, but the debate among competing companies was which route to take? Much like during the expansion of the Interstate highway system, everyone wanted the train to come through their state. The northern states wanted it to go through them, and the southern states likewise. It wasn’t until the Civil War erupted that the debate was settled by Abraham Lincoln – the rail line would go through the north.

Lincoln signed the Pacific Railway Act in 1862, awarding land grants and bonds to two companies to build the railway. Both the Union Pacific and Central Pacific Railroad companies were promised $48,000 in bonds for every mile of track that was completed. The Union Pacific railroad started by laying track down from Omaha going westward, while the Central Pacific started in Sacramento, winding its way through the Sierra Nevada mountains and into Nevada on its way east. No meeting point was agreed upon, but both company wanted to go as far as they could before meeting.

The companies were so committed to push as far as they could, that they actually overlapped in Utah before an agreed upon meeting point was decided by Congress in April 1869. It was to be Promontory, Utah.

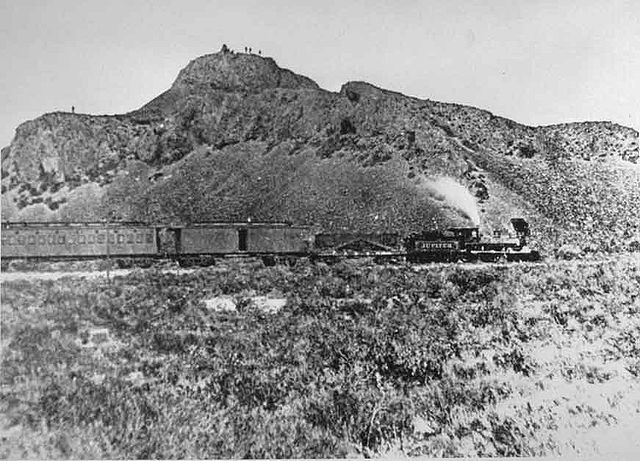

(The Jupiter leads the train that carried the spike, Leland Stanford, one of the "Big Four" owners of the Central Pacific Railroad, and other railway officials to the Golden Spike Ceremony.)

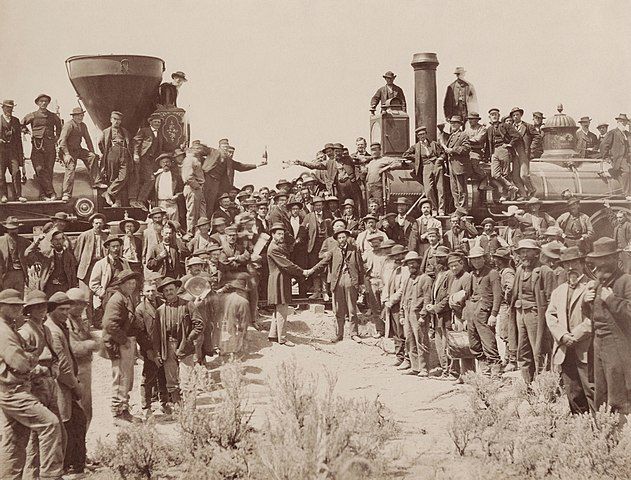

Many remember learning in elementary school the details of the historic reunion of the two rail companies. California Governor Stanford represented the Central Pacific Railroad, and Thomas Durant, president of the Union Pacific, met at Promontory with four ceremonial rail spikes, which were driven into a laurel rail tie. Two spikes were made of gold, one of silver from Nevada, and one of iron from Arizona.

There was much rejoicing after the ceremonial spikes, but the line wasn’t completed just yet. After removing the ceremonial rail tie, another was put in its place with three iron spikes driven in. The last spike had a telegraph line attached to it, so the entire country could hear the rail line’s final spike driven in.

With the completion of the railroad, the once-arduous trip could be completed in less than a week. But more than just creating a meeting point that would become a tourist destination and historical footnote, the location of the ‘Golden Spike’ as it would become known has had prolonged impact on Utah.

Impacts on Utah

It would be impossible in an abbreviated space such as this to detail all the impacts of the transcontinental railroad or the life its construction created – from the hiring of the 15,000 Chinese migrant workers to the impact on Native American populations – but having the railroad meet in Utah has had a significant effect on Utah agriculture, culture and economy.

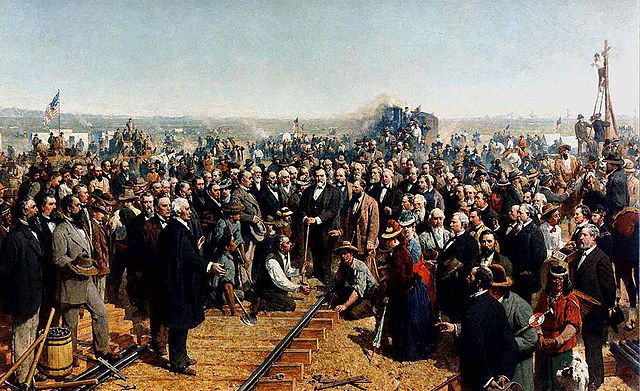

One such impact was with the Union Pacific railroad company contracting with Brigham Young to have workers lay track through the Wasatch Mountains. This stretched from Echo Canyon in Summit County, all the way to the Great Salt Lake. Many of the construction projects still exist today. A problem came when the rail company went bankrupt and couldn’t pay Brigham Young and his workers. Instead, it was agreed upon to give Brigham Young rail cars and supplies to connect the city of Ogden to Salt Lake City. Even more important, the company agreed to provide free passage of emigrants from Europe to travel to Utah. A look back at population growth shows that in the ten years after the completion of the rail line, Salt Lake City’s population doubled, and then doubled again 10 years after. Surely this free ride played a role. (Photo by Thomas Hill)

Changes to the Line

Promontory lost a little of its prominence in 1903, when the Lucin Cutoff was installed. This enabled trails to travel directly over the Great Salt Lake, instead of looping around it. The rail line north of the Great Salt Lake was abandoned completely in 1942, paving the way for the permanent causeway built in 1955, which altered the biology of the lake forever.

Creating New Industries

While the rail line was important economically in Utah for the creation or advancement of industries related to cement, minerals, mining, and even trash removal, it played a significant role in Utah’s agricultural and food processing industries.

Chief among these processing industries was fruit and vegetable canning. According to the Utah History Encyclopedia, Utah’s canning industry started in the 1880’s, not long after the railroad was completed. Hitting its peak in the 1920’s, Weber, Davis and Cache Counties led the way by preserving foods and then shipping them by rail to higher population centers. Box Elder and Utah Counties got into the mix as well, with Utah-grown tomatoes and peas leading the way.

While companies like Del Monte set up shop to preserve Utah fruits and vegetables, they weren’t the only food product that thrived. Flour, sugar beets, and grain storage also benefited from having the railroad close-by. At one time, more than 45 canneries made their home in Utah.

Milk canning was another agricultural industry that prospered during this time of increased demand. Without the advantages of refrigeration, condensed milk was a way of preserving dairy for long periods of time needed for transportation. In Cache County alone, it was responsible for using the milk of more than 3,000 dairy farms, helping solidify that’s region reputation as a dairy powerhouse that remains to this day. Brands such as Carnation and Sego Milk (the Utah Condensed Milk Company) established an industry that consumed up to half of the state’s milk supply. Milk would be shipped by rail to processing plants, and then out via rail again to markets for consumption.

The livestock industry also benefited from rail traffic as well, with 1945 being the peak year for cattle, sheep and hogs.

While the railroad helped put the Utah produce and milk industries on the map, it also contributed to its demise. With the invention of refrigerated railcars, the advantages found in canning were replaced.

Transportation would continue to evolve throughout our history and the industries it has supported have continue to evolve along with it. Many have turned to local farmers markets to get the best Utah produce available, and yet Utah milk from Cache Valley continues to find its way to shelves abroad through preservation techniques. Despite the changes and the new, improved ways to get food to market, it’s hard to ignore the cultural and economic contributions the railroad made during this celebratory year.

To help showcase the history and importance of the Transcontinental railroad and driving of the ‘Golden Spike’, many events have been taking place – leading up to the big day of May 10, 2019. For those looking for a more hometown interpretation, residents of Box Elder County are putting on a theatrical production known as The Crossing – Box Elder’s Golden Treasure. The production will take place at the Old Barn Community Theater in Collinston, Utah on May 7th and 8th, and is free to the public. It will focus on the early history of the county – from the rich Native American heritage and Pioneers, to the Stage Coach & Freight Wagons and the emergence of trains.

For more information or to secure reservations, contact Laura Selman at 435-452-1674 or fselman@citlink.net. For more information on other events taking place, visit spike150.org. There may be other recent events that have captured the media attention of Utah, but it’s hard to forget the impact of that fateful day in 1869.

Want more news on this topic? Farm Bureau members may subscribe for a free email news service, featuring the farm and rural topics that interest them most!