Lessons From My Grandad

Author

Published

9/9/2022

When my grandad was 12, his mother died.

His father, an abusive drunkard who struggled to provide at the best of times, promptly lost their house and land.

The girls were farmed out to different relatives, but the boys, Art (my grandad) and his older brother John (15), were considered “old enough” to fend for themselves.

Their father rented the two boys a house in town for a while, but eventually fell behind on those payments too and they were evicted. John had found work with a local family and was able to board with them, but times were hard during the Great Depression, and they couldn’t take Art.

So it was that on Christmas Eve, at 13 years of age, my grandad found himself homeless.

He made a plan that he would go back to their old family house, now vacant, to at least spend the night and figure out what to do. He knew there would still be some dishes and blankets in the house.

It being Christmas Eve, John took him to see a movie at the local theater, and then rode him to the edge of town on his bike. They said their goodbyes and Art started off on foot to their old home.

Soon a truck pulled up beside him.

“Where are you headed?” the driver, Mr. Freston, asked.

“To the old Taylor place,” Art answered.

“Nobody lives in that house.”

“I know.”

“Well, you’d best jump in here with me.”

---------

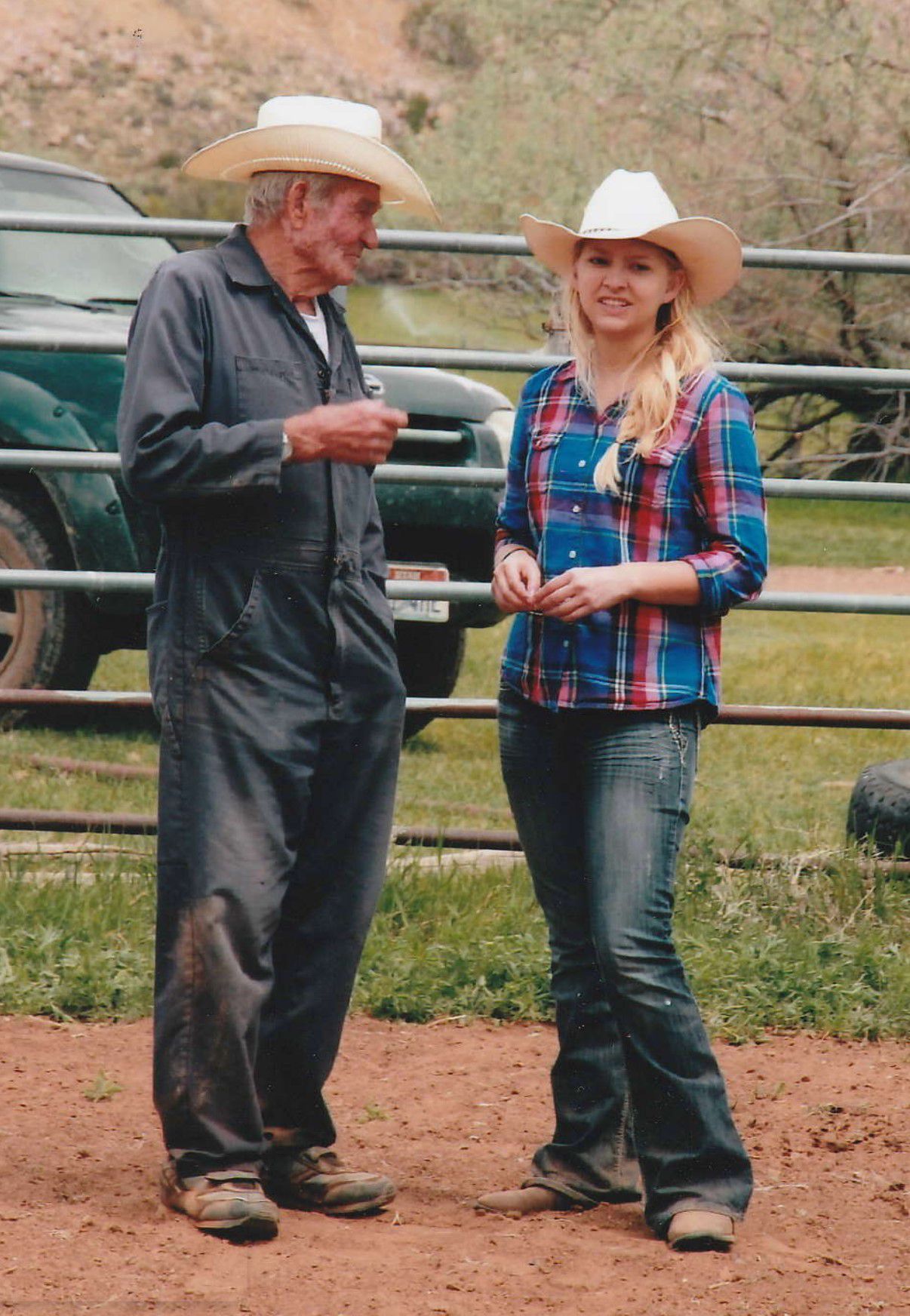

I miss the way he pronounced my name. Not three distinct syllables, Joo-lee-a, but two smudged together with a slight twang: Jul-ya.

I miss seeing him walk across a field with his shovel over his shoulder.

I miss his sheep call.

I miss his expansive knowledge of our tiny town: who cheated whom out of water in 1981, where the old stagecoach station was, whose son was a good-for-nothing, where exactly you needed to shift when climbing that hill so you could grab a higher gear.

He never missed an article I wrote.

Grief has an inconvenient way of showing up. I hardly cried at my grandparents’ funerals, but months later I find myself blinking away tears in Wal-Mart, while sweeping my floors, or talking with a neighbor about lessons I learned from him.

From Destitution to an Abundant Life

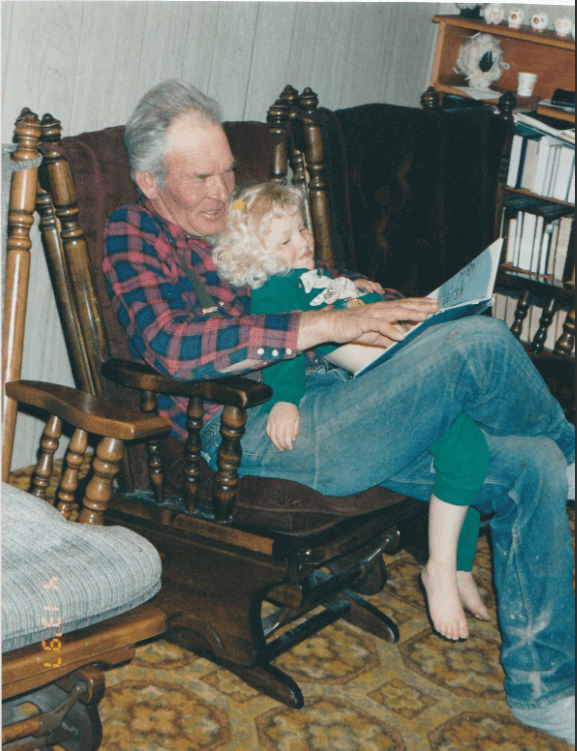

After spending that Christmas morning with the Frestons, Art passed from farm to farm, trading work for room and board for the next couple of years, until he landed permanently with a prominent ranching family in Duchesne, Elmer and Arwella Moon.

The Moons took Art in and loved him like a son. From their home, he graduated high school, served a mission for the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints, and served in the military in Korea during reconstruction.

When he returned from his military service he married my grandma, KaraLyn. He always said he wished they hadn’t had an engagement, because that was three more months that he could have been married to her! He knew he wanted to farm so he bought a small farm from his father-in-law in Roosevelt and started working at the Duchesne Post Office to make ends meet. He bought different parcels of land to create his ranch throughout the years, and worked his way up at the post office until he became Postmaster.

By the time he died he had cultivated more than 1,000 acres, a few thousand acres of rangeland, raised eight children to adulthood, lost two babies, had 30 grandchildren and 41 great grand-children – along with raising sheep, cows, pasture, and countless crops of alfalfa.

He was never bitter toward his father, or any of the people who had mistreated him as a boy, but he was passionate and staunchly stubborn in his opinions, and he had many opportunities to air them. He served as the County Farm Bureau President, on the Duchesne County Water Conservancy District (where he was awarded the Golden Shovel Award), Duchesne City Council, Duchesne County School Board, the American Legion, as a Bishop in his church, and even as an irrigation specialist to Tajikistan where he helped teach irrigation principle with the Winrock International Farmer-to-Farmer program.

He was who he was. He always said, “If you have to scream to the world that you’re something, you’re probably not.”

A Continual Guiding Influence

Sweating as I knelt under a huge rose bush, gabbing at the dirt around its base alongside my neighbor on a warm summer morning was not how I had planned to start the day. But my neighbor had an itch to remove the bush and I had volunteered to take it, so our impromptu rose removal project was underway.

I stood up, wiped my brow, and leaned on my shovel.

“You know, whenever I hold a shovel it reminds me of my Grandad,” I said.

“Oh. Why is that?” my neighbor replied.

“He always had one with him,” I responded. “He needed it whenever he was out irrigating the fields. One time he was crossing a canal on a ‘bridge’ that was just two fallen logs; they broke beneath him and he fell into the water below. He was 90 years old at the time. The bottom of the canal was too rocky for him to get his footing so he let the current carry him downstream until he came to a place where he could stand up. But even then, the banks were too high and sheer. He still had his shovel, so he dug steps out of the bank and used them to climb out.”

“Wow,” said my neighbor, duly impressed, “He was one tough man.”

“Yes, he was,” I said.

Once we had successfully transplanted the bush we stood back and admired our handiwork.

“I hope it doesn’t die,” My neighbor said.

“I just need to water it,” I replied. “My Grandad said that once you planted something, you needed to take a bucket of water and crush an aspirin into it and pour it onto the plant every day.”

“What does the aspirin do?” my neighbor asked.

“That’s what people would ask him. And he would say, ‘Nothing! But it helps you remember to put a bucket of water on it every day!’”

I laughed, but I felt the tears prick behind my eyes.

Want more news on this topic? Farm Bureau members may subscribe for a free email news service, featuring the farm and rural topics that interest them most!