Waste Wool Works Wonders

Author

Published

4/16/2017

CROYDON – As in most businesses, Albert Wilde wanted to see how he could maximize the value of his family’s sheep business and minimize the waste that took place. The answer came in an unconventional place –the basketball court.

“I was playing basketball with a friend of mine that had a wood pallet business, and he talked to me about the idea of starting a business for yard mulch. He had plenty of leftover wood products, and he was looking for manure to mix with it,” Wilde said.

The two men got together and began a successful partnership of making mulch for local greenhouses and nurseries. While it was nice to find another avenue for the manure from his livestock, the idea got Wilde thinking even further about how to solve another problem his wife presented to him – how to keep house plants and hanging baskets alive while she was out of town?

Wilde, a 6th generation sheep rancher from Morgan County, got to thinking about the wool from his sheep and if it would have any value as a soil amendment. For most sheep ranching families, the value they get from wool can vary depending on the quality, but also the location of where the wool comes from on the animal. Typically, wool from the belly and underside of the sheep is not worth as much, because of the shortness of the strands and the amount of work needed to clean the vegetation and organic matter that gathers in this wool during the animal’s activities.

During shearing time, much of the belly wool goes for as little as five cents a pound, or can even go unsold, which is why it is often referred to as ‘waste wool’. Belly wool can account for approximately 20 percent of the total wool from a sheep’s fleece, so it represents a fair amount of wool that doesn’t generate much return.

Despite some claiming the wool wouldn’t break down in soil, Wilde was convinced there had to be a way to get more value from the waste wool, and so he tried a non-scientific experiment of placing some wool in hanging baskets around his home before leaving for a few days, and compared it with other plants. Though it was successful, Wilde found it impractical to place loose wool around the plants because it could blow away. It was also not very visually appealing. Wilde worked with his mulch partner to use his pellet machine to compress the wool to see if it would make it more user-friendly.

Brian Gold from Pineae Greenhouses in Ogden later approached Wilde to see if he had organic steer manure for another project he was working on, and Albert asked if he’d be willing to try some wool pellets to see if it reduced the amount of water needed in Gold’s tomato plants. While a little hesitant, Gold experimented and found that after seven days, the plants with the wool pellets had retained about 40 percent more water than those without.

Impressed by the early results, the greenhouse wanted to see more information and to find out if the wool pellets added any nutrients to the plants as well. The nursery used the pellets in a trial for its organic tomato plants, using 30 pots with no fertilizer, 30 pots with an organic blood meal fertilizer, and 30 pots with varying amounts of wool pellets.

The nursery researcher was thinking it would be 60 days for the wool pellets to release any nutrition; however, 38 days into the trial, the pots with no fertilizer were not looking good, the blood meal pots fared no better, and yet the ones with wool pellets looked ready to ship out.

Good for Soil

Wilde was convinced he had something special on his hands, and reached out to researchers at Utah State University (USU) to better determine what nutrients could be found in the wool pellets. Jason Barnhill, a USU Extension agent in Weber County, told Wilde of finding only one older European study, in which wool had been used to repel snails. Wilde has since begun working with USU greenhouse researcher Bruce Bugbee to learn additional benefits of the wool pellets, and anticipates the final results of the research this summer.

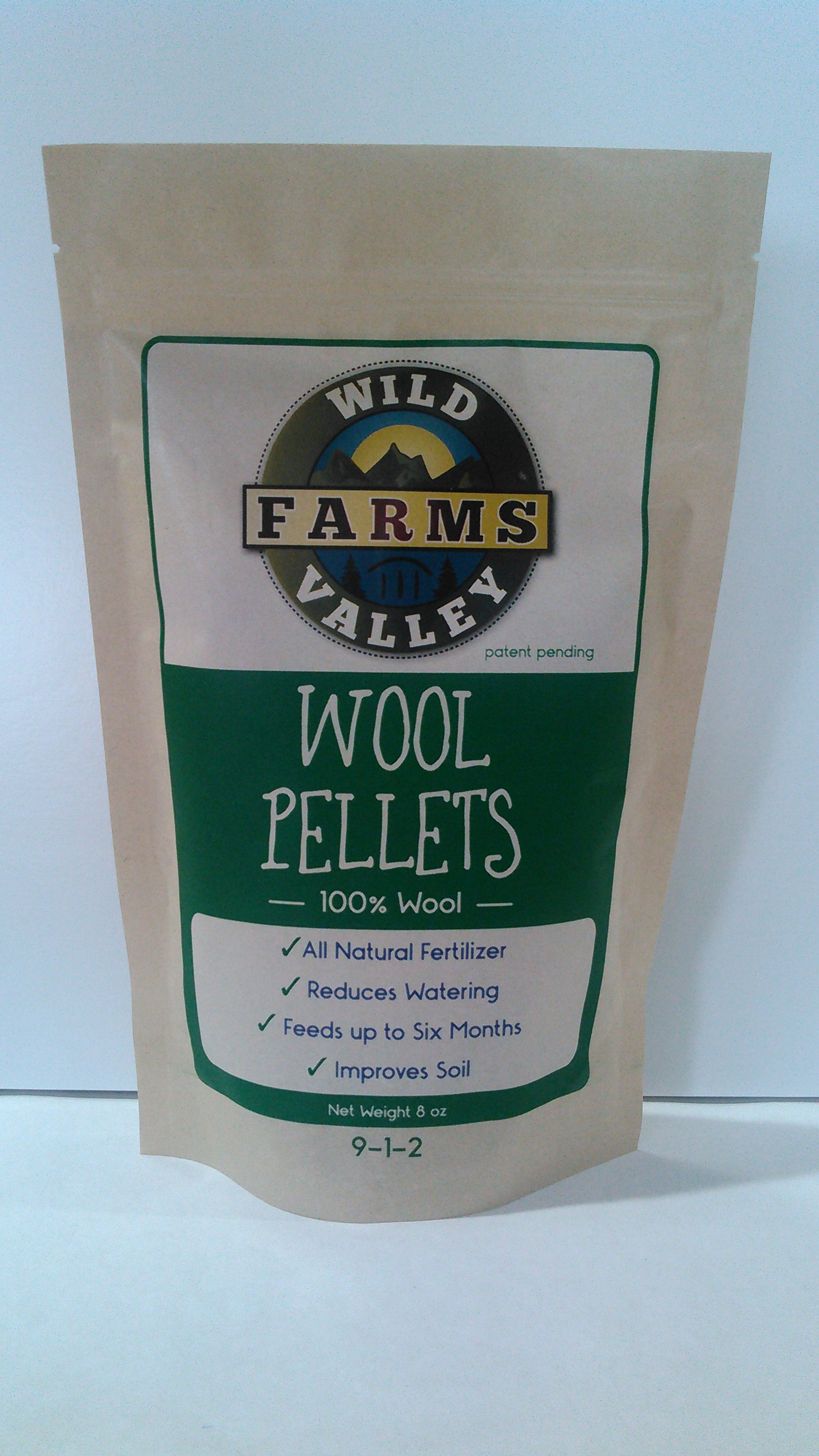

Additional research has found nutritional contents of the wool pellets to include nine percent nitrogen, one percent phosphate, and two percent potash. By taking months to break down, Wilde is hoping to market the pellets as a natural, slow-release fertilizer.

Beyond the nutrients in the wool itself, there are great benefits to be achieved ranging from water savings to soil health. Wool naturally absorbs water – about 20 times its weight – so gardeners and landscapers can conserve more water. As the wool soaks up in the soil, it fluffs up and expands, increasing soil porosity and improving the soil’s ability to retain oxygen.

Good for Ranchers

While Wilde is happy to have found a product that delivers positive results for consumers, he is most happy about what it can mean for those in the sheep industry. Word of successful trials in greenhouses spread quickly, and word-of-mouth marketing led to features on Utah’s Fox 13 News affiliate and articles from bloggers in the U.S. and Canada that went viral. Wilde starting getting requests from local nurseries and others around the country.

With the success Wilde had, he quickly realized he would not have enough wool from his own sheep to mass produce this product – so he looked to his fellow sheep ranchers to buy their waste wool. Rather than paying the going-rate, Wilde looked to improve the bottom line of his fellow sheep ranchers and paid 60-cents per pound for the waste wool. For Wilde, he truly ascribed to the philosophy that a rising tide lifts all boats.

“For the best of the junk wool, you may get .25 cents. The worst of it you get 5 cents. For some, you get nothing at all. We just wanted to raise the market for low-end wool,” Wilde said. “It helps those with larger flocks, by helping on the back end. It also helps the smaller sheep ranchers, because many were just throwing that waste wool away. We’ve even had ranchers across the country willing to give us the wool, if we’d just come pick it up.”

While still in its infancy, Wilde is optimistic his product is poised for continued growth as more research comes back. His wool pellet fertilizer is registered in Utah and Illinois, and he anticipates selling in additional states going forward. Wild Valley Farms Wool Pellets are currently sold in 8-ounce bags for $8.99 and 16-ounce bags for $12.99 on his website. The products can also be found on Amazon.com and Wilde is working on getting them into additional garden shops and greenhouses locally.

Truly innovative in nature, Wilde has a patent pending on his wool pellets and recently attended the American Farm Bureau’s Rural Entrepreneurship Challenge, where he received encouragement and motivation for the future. With benefits to yards and gardens, as well as the sheep industry as a whole, Wilde is hoping the future of wool is far from a waste. For more information about the wool pellets, visit www.wildvalleyfarms.com.

Want more news on this topic? Farm Bureau members may subscribe for a free email news service, featuring the farm and rural topics that interest them most!