Gossner Foods Supporting Community & Troops Through Innovative Business

Author

Published

6/25/2019

The following is an article that was published in 2016. It includes quotes from the former Dolores Wheeler, CEO and President of Gossner Foods, who passed away in 2018.

LOGAN – When Ed Gossner set out to make Swiss cheese in the 1960s, he was told it couldn’t be done in Utah because of feed the cows were eating during the long northern Utah winters. Fifty years later, Gossner Foods produces 20 percent of the nation’s Swiss cheese and has pioneered milk processing to supply American soldiers with a taste of home.

Despite producing such a large amount of the nation’s Swiss cheese – both under its own Gossner Foods label as well as for many other companies – the company wasn’t guaranteed a promising outlook when it started out. It took dedication, hard work, and a commitment to supporting local farmers.

Ed Gossner immigrated to the United States from his home in Switzerland in the 1930s, where his family had been farming for five generations previously. Limited economic prospects led Gossner to come to America in hopes of continuing in agriculture. Ed teamed up with his brother Ernest in Wisconsin, where he had set up his own cheese factory, and learned the art of making delicious Swiss cheese using methods learned in Switzerland. After a few years, Ed moved to California to work with another cheese-making family.

It was in California that Gossner learned to make cheese using milk from cows that had been eating fermented feeds called silage, instead of fresh feed. Previously, it was thought that milk from silage-fed cows couldn’t be used to make Swiss cheese – but Gossner proved them wrong.

While on a trip to Yellowstone with his family in 1941, Gossner passed through the Cache Valley and found it ideal, with its climate and elevation resembling that of his childhood in Switzerland. Within a year, the family had moved to Utah and used milk from their own cows, and those from dairy families throughout Cache Valley.

"We had to get milk from others because we grew fast,” said Dolores Wheeler, President and CEO of Gossner Foods, and the daughter of Ed Gossner. “Farmers were told from other milk processors that [Gossner’s] wouldn’t make it, and if they sold milk to us, they wouldn’t be welcomed back. But they took a risk because we paid them well for their milk.”

The ethic of treating the farmers and their employees well has been a hallmark of the Gossner family, and it has remained with them throughout the years.

“We knew what we wanted to become, but it was a struggle to build the company. We had to outpay our competition for milk for many years,” Wheeler said. “We have always taken pride in taking better care of our farmers and our employees than others do. We need these people! Good people and good milk!”

The family focused on making quality Swiss cheese that had the distinct nutty flavor, and yet was perhaps a little more mild than other Swiss cheeses. Focusing on making this difficult cheese also got the company away from the commodity-based cheeses that their competitors could produce.

“We wanted to be good at something that was hard for others to get into,” Wheeler said. “It’s much riskier and harder to make Swiss cheese.”

Producing great Swiss cheese requires dime-sized or smaller holes (or eyes) that are uniformly distributed in the cheese. Making the cheese requires the use of four different cultures for flavor and the creation of the eyes. The eyes are created from carbon dioxide, which is produced during the 60-day aging process and gives the cheese its distinct look. The flavor can also vary depending on the time of year, because winter milk and summer milk flavor varies based on the types of feed that dairy cows are eating.

After cutting and cooking the cheese for four hours, the cheese sits and ages until it is ready to be packaged. After starting with 100 pounds of milk, Gossner’s will end up with only eight pounds of cheese. Though the yields are less for Swiss cheese than others, it is lower in fat than cheddar, and one ounce can provide 16 percent of the daily protein required in a healthy diet. But advancements in making Swiss cheese only tells part of the story of innovation and supporting its community.

.jpg)

Milk on a Shelf

Through its commitment to quality, Gossner and others help Cache Valley dairies improve the quality of milk until it reached Grade A status, which is the highest level for milk. However, in the early 1980s, Gossner looked to create a new market in the milk industry.

In 1982, Gossner bought into different technology to process milk called Ultra-High Temperature or UHT milk. Approved by the Food & Drug Administration in the early 1980s, UHT processing heats milk to a temperature range of 280-285 degrees Fahrenheit, and then flash cooled. The milk is then put into sterile containers and is ready for sale. Through this process, milk can keep a shelf life of 6-9 months without losing any nutritional value or quality.

This technology was developed in Europe in the 1940s, where its longevity was valued because of the challenges of refrigeration. Rather than storing large containers of milk for a few weeks, customers could have cartons of milk in the pantry, and only use one pack at a time in the fridge.

The milk is sold in quart and ½ pint cartons, as well as eight-ounce drink box sizes that are perfect for kids. In addition to the regular, unflavored milk, Gossner milk comes in chocolate, strawberry, vanilla, root beer, cookies & cream, and orange flavors. The company also makes an eggnog drink this time of year called Holiday Nog, as well as year round sales of ice cream, curds, and cheese at its retail outlet.

Using this technology allowed Gossner’s to ship milk out of state and capture different markets. One customer base that has been with the company since the beginning has been the U.S. military, who valued the longevity and storage capacity of the milk.

“We have one contract that serves several bases in the United States, as well as Korea and Honduras,” said Kelly Luthi, the manager of the UHT Plant in Utah. “We also have another contract for bases in Afghanistan.”

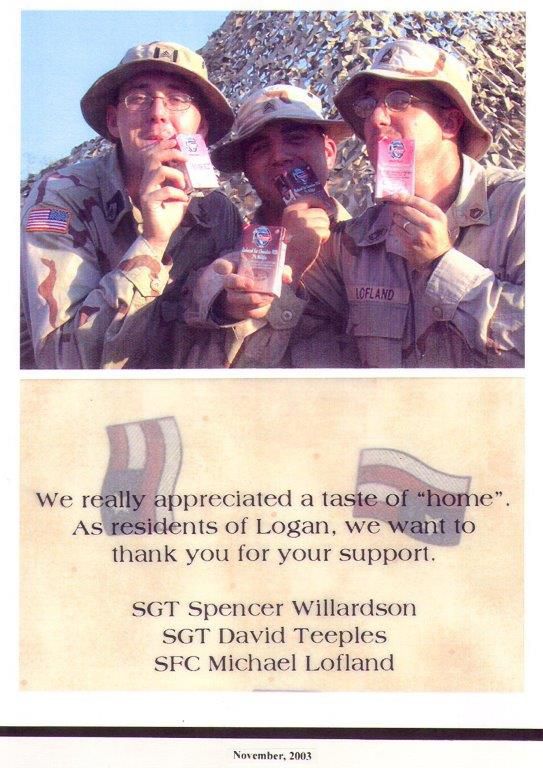

The contract with the military is something Gossner’s prides itself on, as it feels a strong connection to the community. They have occasionally received feedback from the front lines on what the milk has meant to U.S. soldiers.

From a letter sent from a Sergeant Wilken: “We tasted America today. In the fields of Korea on the edge of my cot with the other men in my platoon, we opened a case of the ‘pink milk’ your company makes. We all sat awaiting to receive a carton of this new treat. Simply wonderful. Words on paper cannot describe the happiness ‘little pink milk’ brought to a grown man. The 12 of us agree it was good stuff while it lasted. In the fields of Korea, thank you for making a good product.”

The shelf life also allowed Gossner Foods to land contract to ship milk into Hong Kong, a rarity for a company outside of China. To this day, the Gossner brand remains one of the few foreign competitors to sell to the smaller family-owned stores in Hong Kong.

With the many strong markets far from Cache Valley, Gossner Foods has worked hard to maintain the support of its community, often giving back through sponsorship of events, ranging from the well-known Gossner Foods basketball tournament through Utah State University to the Ag in the Classroom Program.

Despite the accolades the company has received, including being named Utah Manufacturer of the Year, the company receives the greatest satisfaction from serving the community.

“It’s just a joy to see the kids come in [to our tasting room]. There’s just a satisfaction with that reaction,” Wheeler said.

Just as cream rises to the top, Gossner’s unparalleled focus on others is what has really allowed it to rise as a giant in the community.

Want more news on this topic? Farm Bureau members may subscribe for a free email news service, featuring the farm and rural topics that interest them most!