High Path Avian Influenza Update – What’s next?

Author

Published

5/24/2023

Since the first case of the 2022/2023 highly pathogenic avian influenza outbreak was detected in the U.S. – in a turkey flock – on Feb. 7, 2022, the virus has affected 58.8 million birds in 831 flocks in 47 states. All levels of the supply chain have felt impacts from HPAI, from the farmer facing the risk of depopulation, all the way up to the consumer paying record prices for eggs and turkey due to tighter supplies. This Market Intel provides an update of the status of HPAI in the United States including the measures USDA has taken and what steps might be taken to mitigate the risks and impacts of HPAI in the United States.

Then & Now

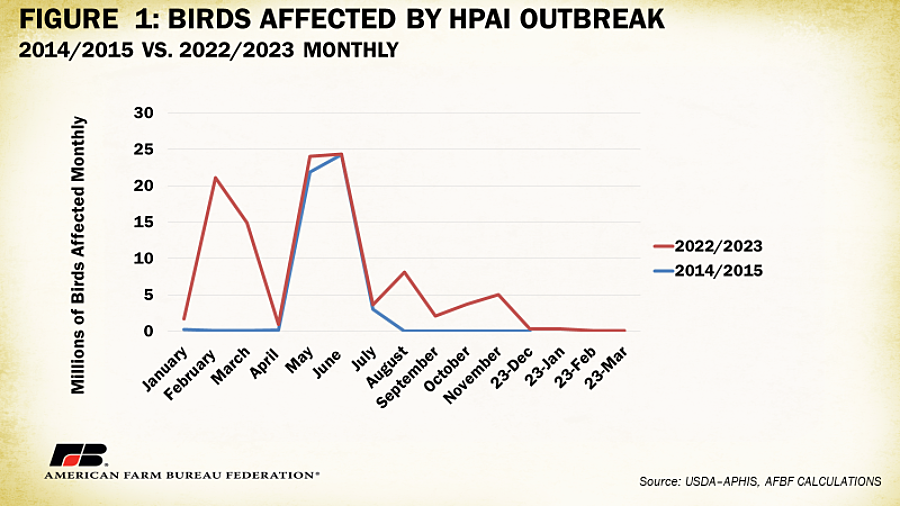

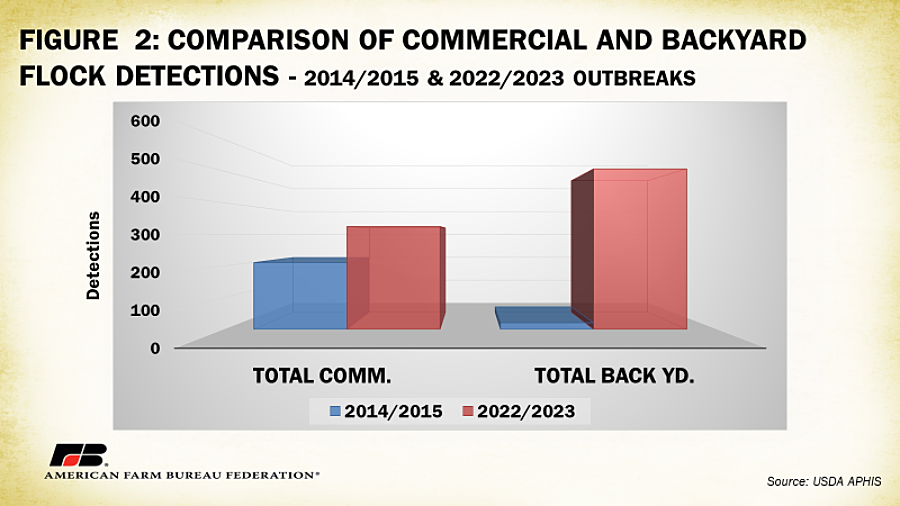

The current outbreak of HPAI H5N1 is much different from the H5N2 outbreak in 2015. The first case of the 2015 outbreak occurred on Dec. 11, 2014, with the last detection occurring on June 16, 2015. Then, the virus accelerated quickly. Affected birds jumped from 0 to 30 million in the first nine weeks. A total of 211 commercial detections occurred, along with 21 detections in backyard flocks. Approximately 43 million egg-layers/pullet chickens and 7.4 million turkeys were affected in 21 states over about seven months.

The current outbreak has been different than the 2015 outbreak in a few ways. First, the current outbreak has been going on for about twice as long as the one in 2015. Second, there have been far more birds affected overall, along with more detections in backyard flocks in the current outbreak. Some of this may be a result of an uptick in backyard flocks during the COVID-19 pandemic.

The HPAI H5N1 virus strain has been circulating the globe for many years and continues to evolve into different groups called “clades.” The current clade, 2.3.4.4b, was first detected in wild birds in the United States in late 2021 and is well adapted to spread throughout wild birds and poultry. This is a new virus for wildlife and strains can continue evolving. Migratory waterfowl, more specifically dabbling or puddle ducks, are the main vector for the virus. Dabbling ducks, such as mallards and teal, are shallow water ducks that feed near the surface by tipping headfirst into the water to graze on vegetation and insects. The H5N1 virus has been found far less in other types of migratory waterfowl.

Response

USDA continues to take a reactive approach to mitigating the spread of HPAI. Reactive measures were able to contain the virus until detections dropped off. Now the amount of the virus being found in wild birds is astounding. USDA has stated that 85% of HPAI is introduced to a flock through outside factors such as wild birds, while only 15% is introduced by lateral movement (from one house to another). USDA is not able to quantify how many cases biosecurity is keeping out of barns. While these reactive measures have been effective, this disease is no longer being seen as something that comes and goes, it is being considered a long-term problem.

USDA’s Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service (APHIS) has three goals for its response to HPAI:

- Detect, control and contain HPAI in poultry as quickly as possible.

- Eradicate the HPAI virus using strategies to protect public health and the environment, and stabilize animal agriculture, the food supply and the economy.

- Provide science- and risk-based approaches and systems to facilitate continuity of business for non-infected animals and non-contaminated animal products.

APHIS follows three principles to contain, control and eradicate HPAI in the U.S. poultry population:

- Prevent contact between the HPAI virus and susceptible poultry. This is the biosecurity portion of the APHIS response. This is accomplished by quarantining infected poultry along with biosecurity procedures to protect non-infected poultry. Under certain circumstances, accelerated depopulation of poultry at risk of exposure may be warranted. Stringent biosecurity measures should include cleaning, disinfecting and avoiding contact between poultry and anything that may have been in contact with HPAI including people.

- Stop the production of the HPAI virus by infected or exposed animals. This is accomplished by rapid mass depopulation and disposal of infected and potentially infected poultry. Proper disposal of depopulated poultry is extremely important. Predatory birds can feed on exposed carcasses, leading to further spread of HPAI.

- Increase the disease resistance of susceptible poultry to the HPAI virus or reduce the shedding of HPAI in infected or exposed poultry. This would be accomplished through the strategic implementation of an emergency vaccine, should a suitable vaccine become available.

Indemnity Program

USDA offers an indemnity program for birds and eggs that are destroyed due to HPAI. This program has compensated growers with nearly $416 million in indemnities. So far in the 2022/2023 HPAI outbreak, only 21 flocks have had repeat detections responsible for a total of $75 million in indemnities. This program does not pay for birds that were killed by HPAI itself, only those that must be de-populated. Since HPAI can move quickly through a flock it is important to promptly report dead birds as soon as they are found to begin the inventory process. USDA indemnity values are based on national average prices and are updated annually using data from USDA’s Agricultural Marketing Service, Livestock Market Information Center and other sources. Click here for more information on the indemnity program and instructions on filing a claim.

Potential Audit Program

APHIS would like to introduce an audit process to fix weak areas in an operation after detections. The party being audited would be responsible for compliance. Operations that do not comply with the required changes would face reduced indemnity payments if a repeat detection occurs.

Proactive Responses

One proactive strategy APHIS has taken is implementing its Defend the Flock education program. This program, founded in 2018, offers free tools and resources to help anyone who handles poultry to follow proper biosecurity practices. APHIS provides resources such as videos, webinars, posters, workbooks and even games and activities in the Flock Defender Toolkit. The toolkit guides producers through protecting their flocks by preventing wildlife access, reducing food and water sources that are attractive to potential carriers of the virus, and disposing of carcasses in ways that do not attract predatory birds.

Vaccination

Another proactive or preventative approach to controlling HPAI is vaccination. APHIS says that more work needs to be done before it can conclude that vaccination is the best strategy, but the modern virus strains are forcing non-vaccinating countries to consider vaccination.

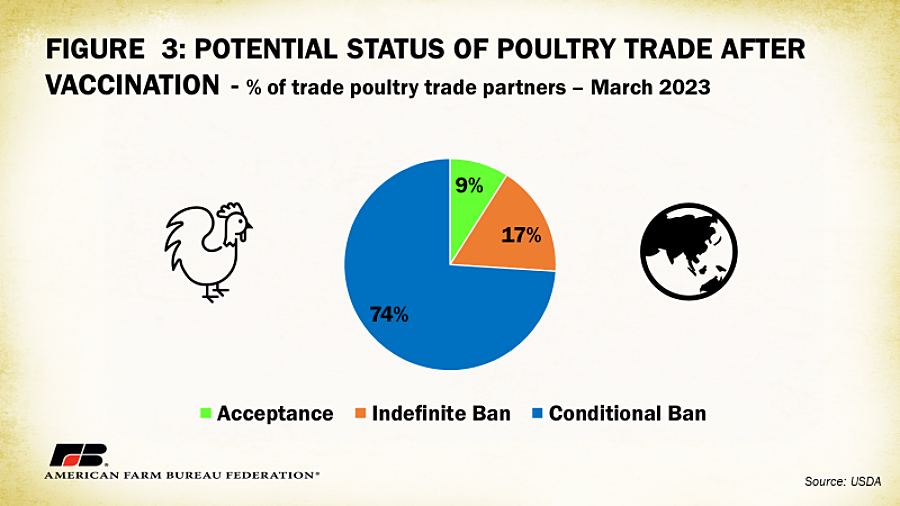

Vaccines for HPAI have been point of conflict across epidemiologists and across countries because countries that vaccinate are often thought of as endemic for the disease and risk losing export markets. Many countries across the world, including the United States, do not allow vaccinated poultry to be imported out of concern that vaccines could mask the spread of the virus by allowing infected birds to slip in undetected. APHIS estimates that 80 trade partners (countries) would be lost if the United States began vaccinating under current trade policies. Using 2022 values, this would result in about $6.2 billion in losses.

Countries that consume most of their poultry products domestically, like China, have used vaccination to combat HPAI for years. HPAI was first detected in China in 1996 and China began vaccinating against the virus in 2002. China’s vaccination strategy has demonstrated effectiveness and has reduced the incidence of H5N1 in poultry and humans but has not eliminated the virus.

A viable vaccine for clade 2.3.4.4b of H5N1 is not expected to be produced for another 18-24 months. The lack of incentive for pharmaceutical companies to make this a priority because of the policy and trade implications of vaccinating flocks is a big obstacle. However, it is more important than ever to have a vaccine available to deploy alongside a vaccination strategy should the outbreak become severe enough.

One concept being introduced as a tool to promote trade is DIVA (Differentiate Infected from Vaccinated Animals). The goal of DIVA is to allow detection of infected birds distinct from vaccinated because trading partners will not accept infected birds. This strategy could be used to assure trading partners that poultry has not been exposed to HPAI.

France has ordered 80 million doses of a vaccine for HPAI. They will be the first to jump into the fire and see how other countries respond. Many countries will be paying close attention to France to see how policies may need to be adjusted.

Cage-Free Production

Nine states have passed legislation that only allows the sale of eggs from hens raised under cage-free standards. Farms that operate using cage-free methods are expected to increase from 31% of operations in 2023 to as high as 50% by 2025. There are trade-offs associated with different poultry housing systems. Housing systems that allow hens to perform natural behaviors, for example, may expose hens to more disease and risk of natural injury, while improving disease and injury control by confining hens may limit a hen’s ability to engage in natural behaviors. Cage-free systems that allow more freedom of movement make it more difficult to consistently vaccinate and/or boost a flock if a vaccination protocol was implemented. Click here for more information on comparing cage and non-cage housing systems.

Summary & Conclusions

The APHIS response to the current HPAI outbreak is proving effective in controlling the spread of the virus. The current virus strain is well adapted to spread through migratory waterfowl and to mutate. Now is the time to develop a proactive plan in case the outbreak becomes more severe. A viable vaccine is still 18-24 months from being ready to distribute. Being labeled as endemic for HPAI is a barrier to vaccination because it could cause costly trade disruptions. The U.S. is not ready to begin using vaccines as a tool to fight high path AI, but it is essential that a plan is ready in case the need arises. One thing is certain, HPAI now is not the same as it was in 2015, and, unfortunately, it isn’t expected to go away anytime soon.

Want more news on this topic? Farm Bureau members may subscribe for a free email news service, featuring the farm and rural topics that interest them most!