The Crucial Role of Farmer Cooperatives and Why Active Participation Matters

Author

Published

7/14/2024

The cooperative business model has been pivotal in the development and stability of the U.S. agricultural industry. Cooperatives provide a platform for farmers to pool resources, preserve market access, share risk and enjoy economies of scale, which is important to maintaining leverage and bargaining power. Cooperatives also provide a unique opportunity for their members to participate in governance activities and management decisions important to ensuring the organization’s decisions reflect the will of its members and holding its executives accountable. This article delves into the cooperative business structure, underscores their benefits and highlights the importance of active farmer engagement in their governance.

Background

What is a cooperative? It’s a business entity owned and controlled by its members, who both patronize the firm and express formal ownership of the assets of the firm through management rights and the right to the firm’s earnings. Management rights are often provided in the form of democratic voting rights, by a one-member, one-vote rule or based on the level a member-owner utilizes the products or services offered by the cooperative business. For example, in the case of a dairy marketing cooperative, voting rights may be based on the volume of milk supplied and marketed through the firm.

The right to any leftover earnings (called residual earnings) in a cooperative depends on two main factors: how much money members are required to invest (capital equity requirements) and how much they use the cooperative’s services. The capital invested by members helps pay for business development and infrastructure costs, which are essential for running the cooperative. Based on these factors, the cooperative can distribute its net earnings to members in two ways. The most commonly used method is patronage refunds, which are based on how much each member uses the cooperative. The second method is dividends, which are based on how much money each member has invested. The ultimate goal of a cooperative business is to further the collective economic well-being of its member-owners.

Agricultural cooperatives can be broadly categorized into several types based on their functions and services:

- Marketing Cooperatives: These cooperatives assist farmers in processing, packaging and selling their products. By pooling the goods they produce, farmers can access larger markets and negotiate better prices. Examples include dairy cooperatives like Land O'Lakes and Cabot Creamery, fruit cooperatives like Ocean Spray and Sunkist Growers and nut cooperatives like Blue Diamond Growers.

- Supply Cooperatives: Supply cooperatives provide farmers with essential inputs such as seeds, fertilizers and equipment. By purchasing in bulk, these cooperatives can offer inputs at lower prices. An example is Southern States Cooperative, which supplies agricultural inputs to farmers in the Southeast. CHS Inc. is the largest cooperative business in the United States and supplies energy, crop nutrients, seed and crop protection products as part of its business.

- Service Cooperatives: These cooperatives offer various services to farmers, including transportation, storage and financial services. Cooperative banks and credit unions specifically serve the financial needs of farmers, providing loans and credit at favorable terms. The Farm Credit system functions as a service cooperative in this manner. Supply cooperatives like CHS and Growmark also offer marketing services for members, which places them under multiple categories.

Some popular consumer retailers like recreational goods provider REI and grocer Shoprite are also both cooperatives. For REI, members pay a one-time fee to join and receive benefits such as annual dividends based on their purchases, exclusive sales and access to outdoor events and classes. Individual Shoprite stores are owned and operated by independent retailer members. These member-owners benefit from collective purchasing power, shared resources and marketing efforts, which helps them compete with larger supermarket chains.

Why be a Cooperative Member?

Any decision to become a cooperative member is generally dependent on a belief that membership will result in an economically preferable outcome. In general, individual farmers are at a disadvantage when it comes to access to information about buyers and sellers, access to large sums of capital and the ability to negotiate contracts and prices. A dairy farmer who has invested in milking equipment and milk cows cannot suddenly shift their production to produce another product if milk prices are low. Sticking with this example, dairy cows do not stop producing milk when prices drop, their milk must find a market or be dumped. Therefore, a marketing cooperative, in this circumstance, reduces the costs associated with the dairy farmer’s specialized product by providing market power (through the coalition of multiple farmers) and market access. The same concept can be applied to growers of nuts, fruits and vegetables and any other crop. Generally speaking, marketing co-ops will accept and market all the supply produced by their members. Guaranteed market access is often cited as the number one reason farmers join and maintain their cooperative membership.

Being part of a cooperative also means that farmers can pool their resources to achieve economies of scale. This means that by working together, they can reduce costs and increase efficiency in ways that wouldn't be possible individually. This is apparent in the structure of a supply cooperative, which can buy supplies in bulk at a discount and offer those supplies to members at a reduced cost. Many marketing cooperatives purchase their own processing and packaging facilities, acquisitions that would otherwise be untenable for one producer. Additionally, pooled resources often result in the ability to hire professional staff to improve the effectiveness and efficiency of a cooperative. This could include marketing staff that focus on contract and price negotiation and brand management that allows members to capture the value of selling under a consumer-recognized brand.

Governance responsibilities, such as voting on the board of directors (BOD) may also provide members a participatory satisfaction not shared in a more traditional producer- independent buyer relationship. In most U.S. cooperatives, the management team of hired staff, led by the CEO, handles day-to-day decisions, while the BOD, made up of current members, oversees the CEO's performance. Voting for the BOD allows members to have some managerial control and to hold the executives accountable, reducing risks for member-owners. However, this only works if members understand and are kept aware of the complex decisions required to run the cooperative. The division of decision-making between the BOD and management means that formal management authority lies with the BOD, but perceptions of real authority can shift depending on member engagement. How often members engage with the cooperative affects how much input they have in its efficiency and success.

Cooperatives also contribute to the development and stability of rural communities by creating jobs, supporting other local businesses and investing in community infrastructure. Traditional investor-owned firms often extract value from areas of high agricultural production and shift it to their stockholders who often reside in urban areas. Cooperatives often counteract this by providing income to their investor-owners, allowing more of that wealth to remain local and near the source of production supply.

Why is Active Engagement Important Yet Challenging?

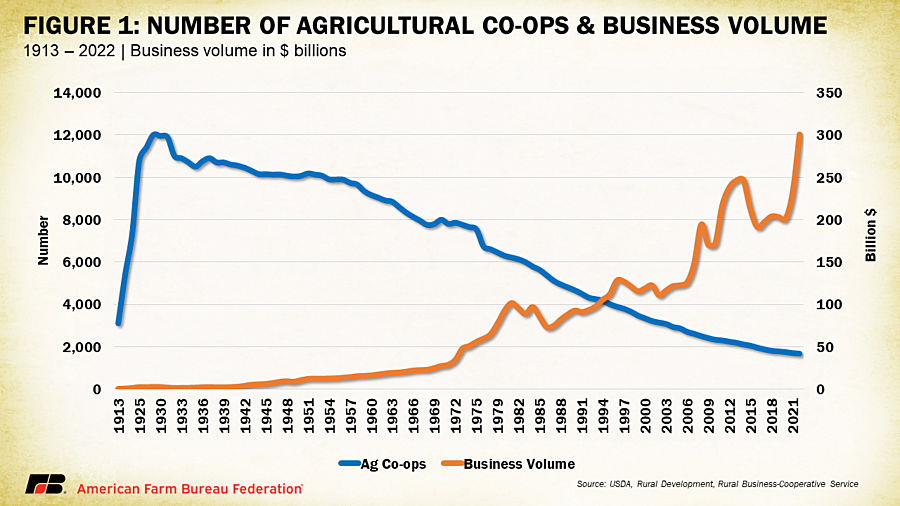

As described, cooperative members are granted governance rights that allow them to participate in the management of the organization. A cooperative’s bylaws will specify the structure of its board of directors, its composition, term dynamics, responsibilities and power limitations. Farmer-members are then obliged to exercise those control rights by voting for directors, on large changes in the business (such as mergers) and on any other decisions defined by the bylaws. Like any form of representative government, the governing body (BOD) will only represent the will of those who vote and/or are engaged. Engaging can be difficult, however, especially as organizations get larger and more interests are at play. Data from USDA’s Rural Business-Cooperative Service shows there were 1,621 agricultural cooperatives in 2022, down 86% from 1929 when the total number peaked at 12,000. During the same timeframe the volume of business has increased from $2.5 billion to $300.56 billion (which includes sales, service and other operating income, patronage refund and non-operating income).

Over this period, many cooperatives merged, bringing in more members in a wider and wider geographic distribution. As new members are added, the membership of a cooperative becomes more diverse with farms of different sizes, differing production and marketing characteristics and different general interests. At times these interests may clash, making the job of effective governance more difficult. Members may feel they are not being adequately represented. Additionally, communication of important governance decisions or coverage of a director’s actions can easily become diluted in the structure of a cooperative. This means members may not have the best information available to make an informed vote or to effectively engage in their cooperative. It is therefore extremely important that member-owners actively maintain communication with their elected representatives within their cooperative.

Failing to actively engage upward puts member-owners at risk of being left out in decision-making activities. Dissatisfaction with the direction of a cooperative or decisions being made by their management team should be checked by ousting directors that do not reflect the interests of members. Newly elected directors can then lead management staff changes needed to shift the direction of a cooperative.

The ability for famers to come together under a cooperative structure is partly granted by the Capper-Volstead Act (1922), which provides partial immunity from antitrust liability for joint ventures between groups of producers. Cooperatives are often viewed as one producer in legal situations, giving them certain flexibilities. For instance, in the Federal Milk Marketing Order system, cooperatives are exempt from certain minimum pricing requirements. Since the entity is owned and governed by producers, payment decisions made by the cooperative should reflect farmers’ interests. This, however, only remains true if members are actively engaged and decisions reflect the will of the cooperative’s membership. All cooperative members have some stake in the assets of their firm and therefore are incentivized to promote good governance behaviors.

2022 Cooperative Statistics

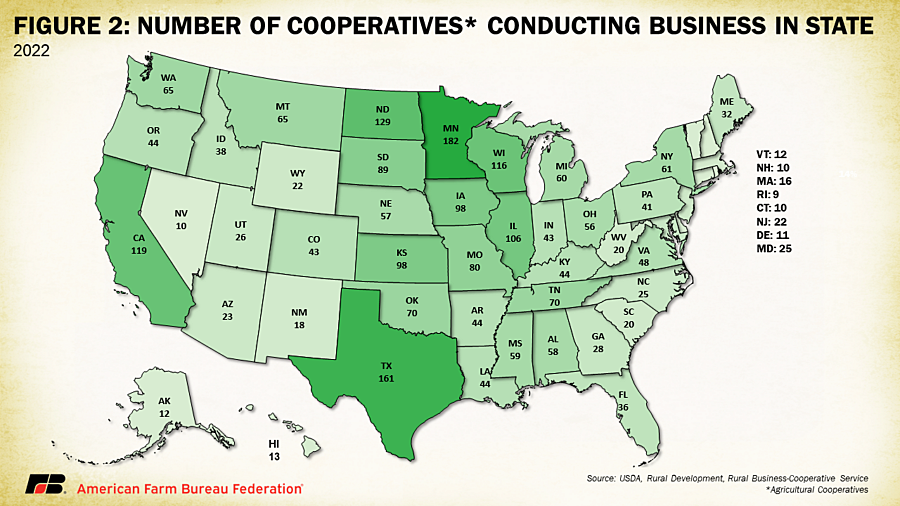

The latest available data from USDA's annual survey of the nation's agricultural cooperatives is for fiscal year 2022. According to the survey, there were 1,671 agricultural cooperatives in 2022, a decrease from 1,699 in 2021 — a reduction of 28 cooperatives (1.6%). USDA attributes this decline primarily to mergers aimed at achieving greater economies of scale and expanding regional reach. Over the past decade, the number of agricultural cooperatives has dropped by 23.6%. Minnesota ranked first in terms of number of agrocultural co-ops doing business in the state in 2022 (182 co-ops), followed by Texas (161) and North Dakota (129).

In 2022, 867 cooperatives (52%) were primarily involved in marketing commodities, while the remaining 804 comprised 696 farm supply cooperatives and 108 service cooperatives. Among the marketing cooperatives, 348 cooperatives focused on grain and oilseeds, 115 on cotton and cottonseed, 97 on fruits and vegetables, 89 on milk and milk products, 53 on livestock and poultry (including eggs), and 38 on fish. The other 127 cooperatives marketed a variety of commodities, including wool, dry beans and peas, nuts, rice, tobacco and various other products.

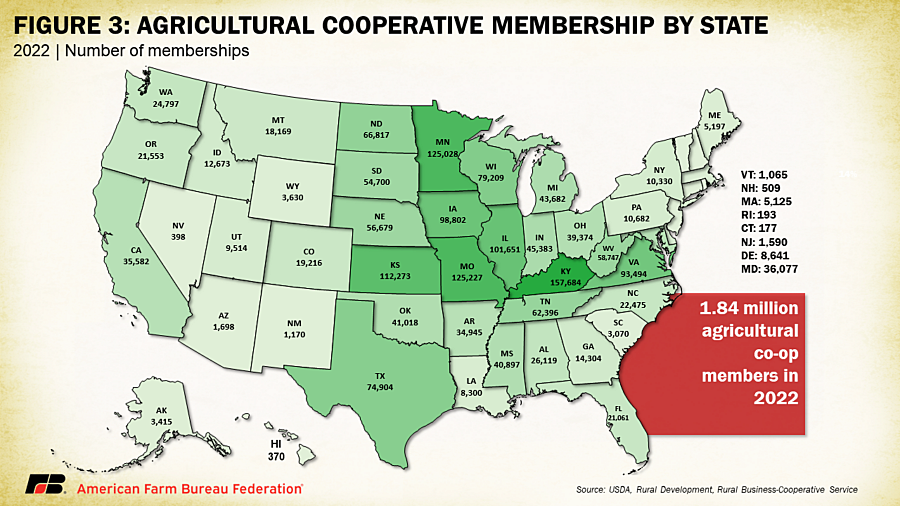

Cooperative memberships were reported at 1.84 million in 2022, down by 4,597 members from 2021. Many farmers are members of more than one cooperative meaning memberships may double-count individuals. Kentucky had the most cooperative memberships in 2022 with 157,684, followed by Missouri (125,227) and Minnesota (125,028).

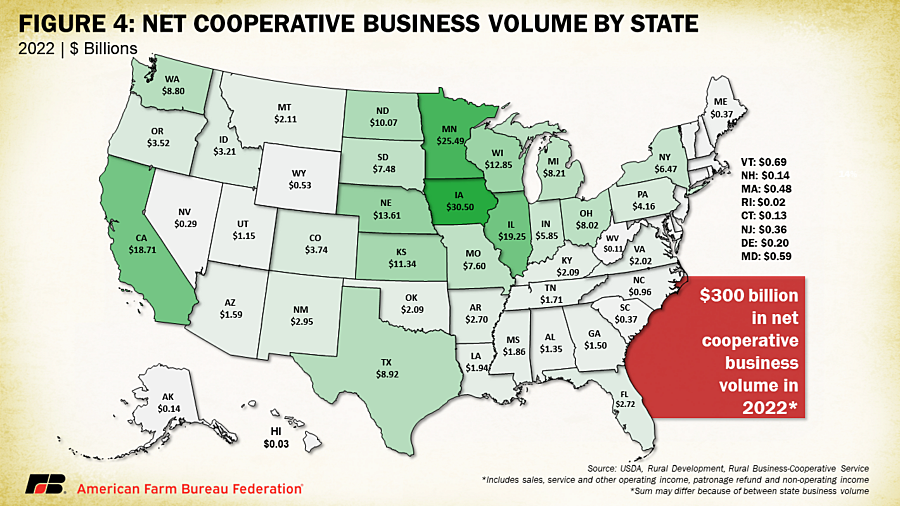

In 2022 cooperatives achieved the highest revenue year ever with over $300 billion in total gross business volume. This record number is linked to the year’s high commodity prices. By co-op sales that occurred within each state, Iowa yielded the highest ag co-op business volume with $30.5 billion, followed by Minnesota ($25.5 billion) and Illinois ($19.25 billion).

The database shows the longevity of the remaining agricultural cooperatives: 391, or 23.4% of all agricultural cooperatives, are 100 or more years old. Fifty-four percent (903 co-ops) are 75 years or older and 77.3% are more than 50 years old.

Conclusion

Agricultural cooperatives play a vital role in supporting the U.S. agricultural industry. By providing a platform for farmers to pool resources, share risks and access markets, the cooperative model not only helps farmers reduce costs and improve efficiency but contributes to the stability and development of rural communities through a grassroots management structure. Active engagement from members is crucial for the effective governance of cooperatives, ensuring that decisions reflect the collective interests of member-owners. Despite challenges such as the diverse interests of a growing membership base and corresponding communication shortfalls, the cooperative structure remains important to fostering economic well-being and resilience among producers. The continued success and adaptability of agricultural cooperatives, as evidenced by their significant business volumes, consumer-recognized brands and long-standing presence, underscore their importance in the U.S. agricultural sector.

Want more news on this topic? Farm Bureau members may subscribe for a free email news service, featuring the farm and rural topics that interest them most!