Debunking H-2A Myths

Published

11/29/2024

The H-2A Temporary Agricultural Workers program – commonly known as H-2A – is the leading source of temporary and seasonal farmworkers in the U.S. H-2A workers, who come from many countries but mostly Mexico, are vital to many types of farms, particularly for specialty crops that are not machine-harvested. This Market Intel addresses some of the most common myths about the H-2A program, drawing directly from the Immigration and Nationality Act (INA) that authorized the program in 1952.

1. Myth: H-2A workers stay in the U.S. long-term.

H-2A workers must “perform agricultural services of a temporary or seasonal nature.” In implementing the INA, the U.S. Department of Labor (DOL) has restricted H-2A use to both seasonal and temporary work; petitions – the applications and job contracts for H-2A workers – may only last up to 10 months, but the average contract is only 6 months. This has created a barrier to utilizing the H-2A program for industries like dairy or nursery that experience labor shortages for more than 10 months. However, a worker who holds a H-2A visa may take different employment contracts to remain in the U.S. for up to three years, if they utilize one-year extensions. Overstaying a visa is rare – less than 2% of all nonimmigrant visa holders, of which there are over 80 programs, stay longer than the length of their visa. If over 10% of nonimmigrants from one country overstay, the entire country can be found ineligible for H-2 visa programs.

2. Myth: H-2A workers take American jobs.

The first step of petitioning to employ H-2A workers is proving that “there are not sufficient workers who are able, willing, and qualified, and who will be available at the time and place needed, to perform the labor or services involved in the petition.” This is accomplished by performing domestic employee recruitment through the state’s, and often surrounding states’, workforce agencies. Employers must hire any American applicant – regardless of qualification – who applies before and up to halfway through the H-2A contract period. However, as discussed in previous Market Intels, the participating American domestic workforce continues to decline and to move away from agricultural work. Less than 10,000 job postings out of over 380,000 positions requested in fiscal year 2023 received an application, and when a domestic worker does apply for one of these jobs, they often do not work through the entire production window, if they show up to work at all. If an employer laid off any U.S. worker within 60 days of the petition start date, they are ineligible to petition for the H-2A program unless the domestic worker was offered and rejected the potential H-2A position.

3. Myth: H-2A workers are a form of “cheap” labor.

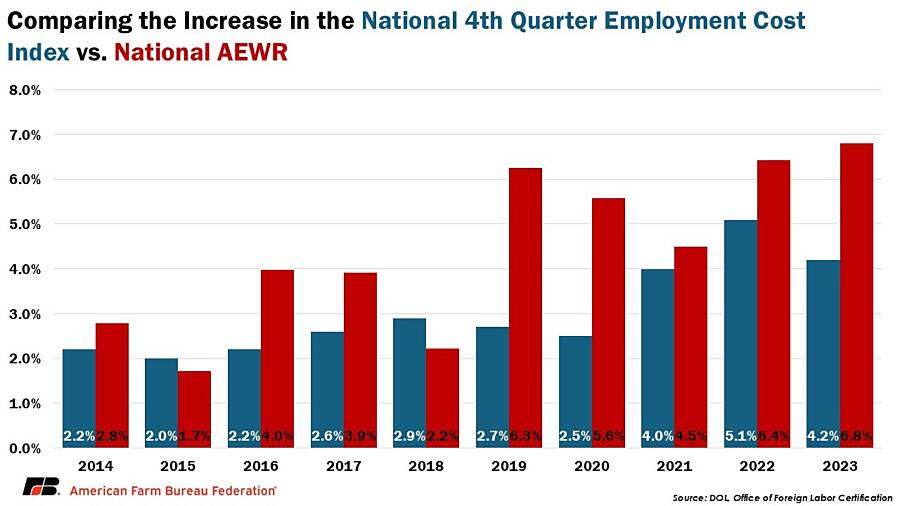

The certification of H-2A workers is reliant upon “not adversely affect[ing] the wages and working conditions of workers in the United States similarly employed.” Rather than evaluating whether there is an adverse effect on wages, DOL pre-emptively requires that H-2A workers are paid the highest of the federal or state minimum wage, the prevailing wage rate, the collective bargaining rate, or the adverse effect wage rate (AEWR). For six job classifications, including farmworkers on crop and livestock operations – which represent 89% of H-2A certified positions – the AEWR is taken from the combined crop and livestock wage in the USDA-administered November Farm Labor Survey (FLS) of the preceding year. The 2025 AEWR will be derived from the next FLS, which will be released on Nov. 20, and will take effect immediately upon publication in the Federal Register. The national average AEWR was $17.55 in 2024. For comparison, farmworkers in Mexico earned $1.59 per hour in 2022. By coming to the U.S., Mexican H-2A workers can earn the equivalent of an entire day’s work at home in one hour in California which has the nation’s highest AEWR at $19.75 per hour. Regardless of how a farmworker is paid – for example, hourly versus piece rate – they must make at least the AEWR for each hour they work. For eight of the past last 10 years, the AEWR has outgrown domestic employment wages. Since 2019, the AEWR has risen an average of nearly 6% a year while other domestic wages only grew 3.7% on average.

As of March 2023, the AEWR has become even more complex. Any H-2A worker who performs a job outside of the six Standard Occupation Classifications (SOCs) included in the FLS combined crop and livestock wage – graders and sorters, agricultural equipment operators, farmworkers (both crop and non-range livestock), packers and packagers, and other agricultural workers – must now be paid full time based on the wage found in the Bureau of Labor Statistics’ Occupational Employment and Wage Statistics (OEWS) mean hourly wage for the general economic conditions, regardless of how frequently they perform that job duty. Yet, the OEWS does not survey agricultural workers. Basing farmworker wages off of this survey means labor costs are being further inflated by non-related industries. While the outcome of these occupations may be similar, the qualifications and requirements differ greatly. For example, a laborer driving a truck of sugar cane from the farm to the mill on local roads must now be paid a wage based on that of commercial driver’s license-holding, long-haul truck drivers.

The hourly wage is far from the only cost for employing H-2A workers. Employers must provide all transportation to and from the United States. While working in the United States, employers are also responsible for providing housing for all employees. USDA reports that housing costs approximately $9,000 to $13,000 per worker. This estimate also does not account for housing requirements that vary greatly by state and can be quite stringent. Transportation costs vary greatly depending on the H-2A worker’s hometown, and with the disaggregation of wages discussed previously, the cost of transporting workers locally has increased as H-2A workers who transport others are now considered chauffeurs.

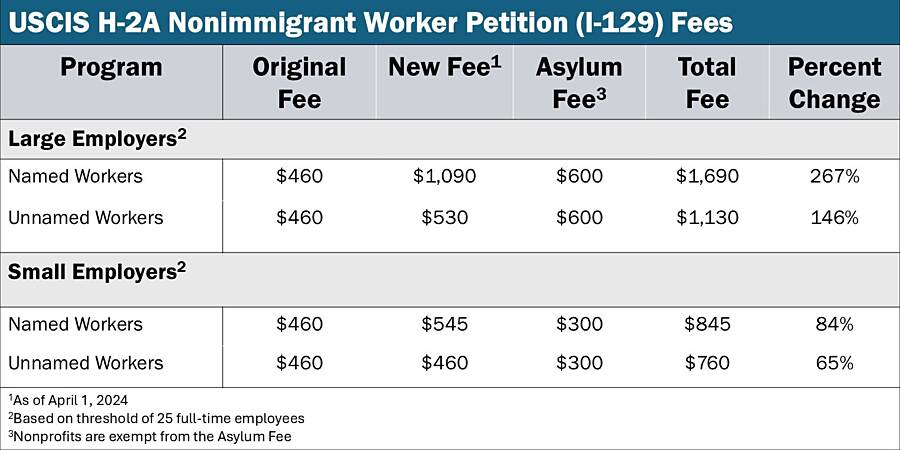

Employers are also responsible for all application fees for the labor petition and each individual worker visa. Fees are collected at each step of the application process from DOL, the U.S. Customs and Immigration Service (USCIS) and State Department. Depending on the number of positions certified, these fees can quickly climb into the thousands of dollars. As of April 1, 2024, USCIS increased their nonimmigrant worker petition Form I-129 fees substantially; most of this increase is a fee to fund an unrelated asylum program. The fee increases vary depending on the size of the employer. Small employers (under 25 full-time employees) who have not yet designated their H-2A workers saw a 65% increase in their petition fees, and fee increases are as high as 267% for large employers with named workers.

Lack of affordable labor compared to international competitors threatens the competitiveness of American products in the international market. The U.S. agricultural trade deficit reached a record $17.1 billion in fiscal year 2023 and is forecasted to continue expanding. This trade deficit is driven largely by specialty crops and other horticultural products, which account for 49% of all imports by value. Domestic specialty crop production, defined as fruit, vegetables and nursery crops, is reliant on H-2A workers. Labor is the number one expense in specialty crop production, accounting for 38 cents of every dollar spent on farm expenses. Ballooning labor costs threaten the viability of specialty crop farms nationwide. Farms that are unable to produce because of labor shortages face production cuts and decisions over whether to shut down. This could avalanche into major losses for rural communities and economies. If fruit and vegetable production continues to decline domestically due to lack of affordable labor, this will further worsen agricultural trade deficits.

4. Myth: H-2A is only used by large employers.

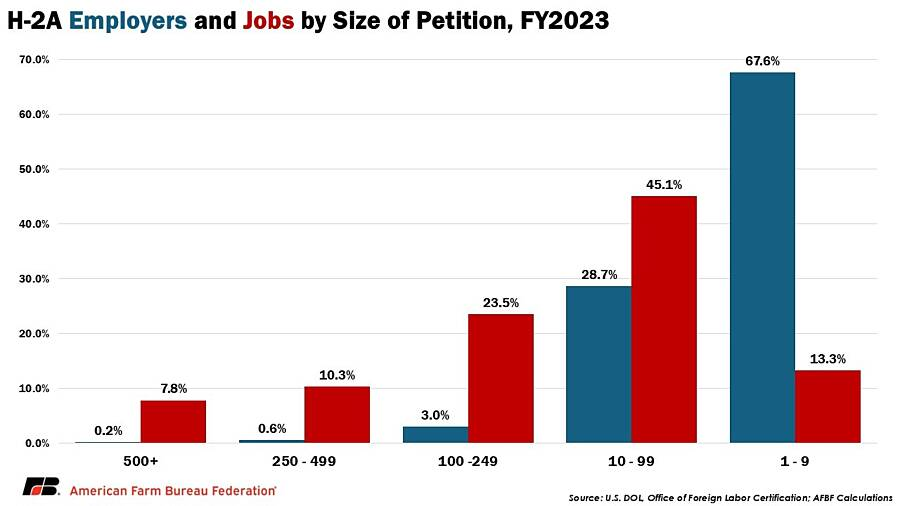

H-2A workers are vital to farms of all sizes. Over two-thirds of H-2A petitions request fewer than 10 temporary workers. Forty-five percent of all H-2A jobs are found in contracts containing between 10 and 99 workers. While some employers may submit multiple positions over a fiscal year, only 1% of all employers employ over 500 employees.

However, because of the growing complexity of H-2A rules and paperwork, there has been a rise in the use of farm labor contractors (FLC). These companies employ more workers, whom they apply for, pay and house, that are then sent to different farms to work. FLCs give farmers access to temporary guestworkers to alleviate labor shortages without having to navigate the H-2A process themselves. In 2020, over 40% of H-2A jobs were employed by FLCs. The rise of FLCs, however, means additional costs to farmers and less direct oversight into the well-being of their employees.

5. Myth: H-2A is a small fraction of the ag labor force.

According to the 2022 Census of Agriculture, over 2.1 million people were hired farm employees, spanning all commodities, jobs and length of employment. In fiscal year 2024, 378,513 H-2A positions were certified, equal to 17% of the total agricultural workforce. In labor-intensive industries such as fruit, vegetable and nursery/greenhouse production, the share is even higher. Nearly 600,000 fewer people were hired to work in agriculture between the 2012 and 2022 censuses. At the same time, the number of H-2A positions certified grew 15% a year on average in those 10 years, going from 85,248 positions in 2012 to 371,619 positions in 2022. The H-2A program is one of the few visa programs without a cap. As the number of H-2A workers continues to grow, so does these workers’ importance to American agriculture.

6. Myth: H-2A workers have no legal protections.

Employers must provide workers with an overview of their rights under the H-2A program in the language most commonly understood by their workers. H-2A employers are subject to state and local guidelines for workplace compensation and safety. Regardless of local requirements, all H-2A employees must be provided with workers’ compensation insurance. H-2A workers are also subject to state overtime wage rules. With the elevated labor costs discussed above, this can result in more employees working less hours so employers can avoid paying overtime wages. However, H-2A workers are protected from employment loss with the “three-fourths guarantee.” This protection requires that employers pay workers for at least 35 hours per week for the entire length of the job contract, even if the work is completed in fewer hours. If the employee works less than three-fourths of the workdays on the contract, the employer must pay the difference to meet the guarantee.

H-2A employment is also subject to safety inspections and state safety standards. Housing must conform to “local standards for rental and/or public accommodations or other substantially similar class of habitation.” These accommodations are inspected by Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OHSA) employees to ensure compliance. Other safety standards include state heat illness prevention rules, first aid requirements or water access.

Violations to any H-2A provisions are handled through the DOL Office of Foreign Labor Certification (OFLC) Ombudsman Program. Concerns are filed with OFLC and investigated at no charge to the filer. The program provides impartial remediation between parties to discuss events of interest. Workers are protected from retaliation or discrimination resulting from a complaint filing, legal inquiry or testifying in a proceeding. Workers may also assert their workplace rights for themselves or others with the same protections from intimidation or discrimination.

7. Myth: The H-2A program must be working great for farmers based on its popularity and growth.

The H-2A program is crucial to helping combat the labor shortages plaguing the agricultural industry. Recent growth in the H-2A program is reflective of declining labor across the economy as the domestic American labor force shrinks.

While the program is vital to agriculture, it could be improved. The costs and administrative burdens associated with the program weaken the practicality of utilizing the program for many farmers. While these costs must be borne in the short run, they change the economics of farming, and risk making many American farmers uncompetitive with imports from low-wage countries.

With eased administrative burdens and lower costs, it is likely that use of the H-2A program would grow even faster than it has been in recent years. As the domestic workforce continues to move away from manual labor, foreign labor sources will become more crucial to maintaining domestic food, fiber and fuel production.

For USDA’s comprehensive guide on applying for the H-2A program, please visit: https://www.farmers.gov/working-with-us/h2a-visa-program.

Want more news on this topic? Farm Bureau members may subscribe for a free email news service, featuring the farm and rural topics that interest them most!